This is a non-exhaustive overview of several of our soil-based watercolors. Please reach out or comment below if you have any questions or anything to add.

Hematite (64)

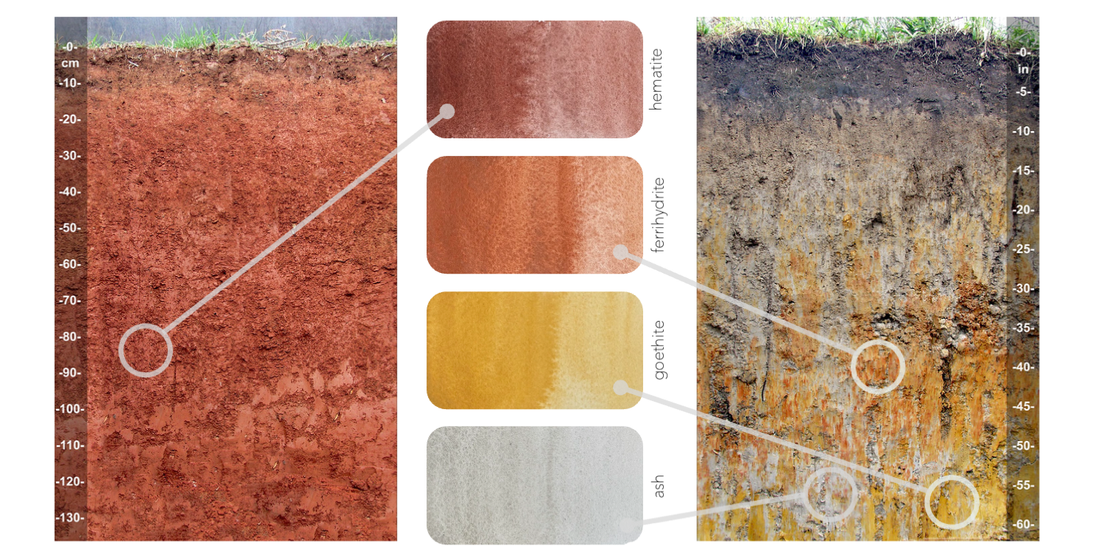

This highly pigmented earthy, red, soil-based watercolor is named for the mineral it’s pigmented with. Hematite is a non-magnetic iron oxide that can be many colors (you’ll see this mineral name again as we explore other soil-based watercolors) – from red to yellow and purple to brown. The name hematite is derived from the Greek word, haimatites, meaning blood-like. In soils, clay-sized hematite is a secondary mineral – meaning it formed from primary minerals through biogeochemical reactions. This iron oxide is quite resistant to weathering (processes that change a mineral into something else) and therefore is common in wet, tropical environments (among many others) where more easily weatherable minerals have been altered or weathered out. The Clifford series in the southeastern US contains hematite dispersed throughout the profile.

Ferrihydrite (65)

Goodness, where to start? Technically, ferrihydrite is not a mineral but rather a proto-mineral. It is classified as such because it is poorly crystalline, lacking a defined structure. Instead, it is an amorphous gel, but – it behaves as a solid such that we can use the dry, clay-sized form to make soil-based watercolor paint. Ferrihydrite is also an iron oxide but one that is dynamic – able to transform with changes in the soil environment. Under saturated conditions, the iron can be reduced by microbially mediated reactions and appear colorless. When exposed to oxygen – the reduced iron is oxidized and we visually see a delightful orange color. The Coxville series shows great expression of the temporal ferrihydrite concentrations, streaked across the soil profile.

Goethite (63 aka #7)

Pronounced grrrr-tight, this strong, earthy, yellow iron oxide mineral makes an excellent soil-based watercolor. It is found in soils all over the world and has long been important as a pigment source – being identified in Lascaux Cave where artwork is dated 17 to 22,000 years old. Geothite forms from biogeochemical weathering of iron-containing materials and is common in highly weathered systems because it too is resistant to weathering. The Coxville series contains striking goethite in the lower part of this seasonally saturated soil.

We also fondly refer to this color as #7 because when I think of the number 7, this is the color I see. Any other folks with synesthesia?

Ash (68)

Despite the name we’ve assigned to this soil-based watercolor, it’s not made with ash – it just looks like “ash.” This light gray ocher contains small amounts of iron oxides and calcium carbonate. In soils, we observe gray colors where mineral grains are uncoated by other, more pigmented colors (e.g. iron oxides). In this Coxville series soil profile, the subsurface shows zones of reduction (anaerobic conditions) where the uncoated mineral grains are observable as gray.

More information about our soil-based watercolors can be found here. Soil profile photos from John A. Kelley, USDA-NRCS. Information distilled from here and all past experiences learning and teaching on the topic. Links to more information about soils can be found here.

1 comment

Thanks this was really helpful. Love the colors created.